Electric vehicles and heat pumps are reshaping power demand

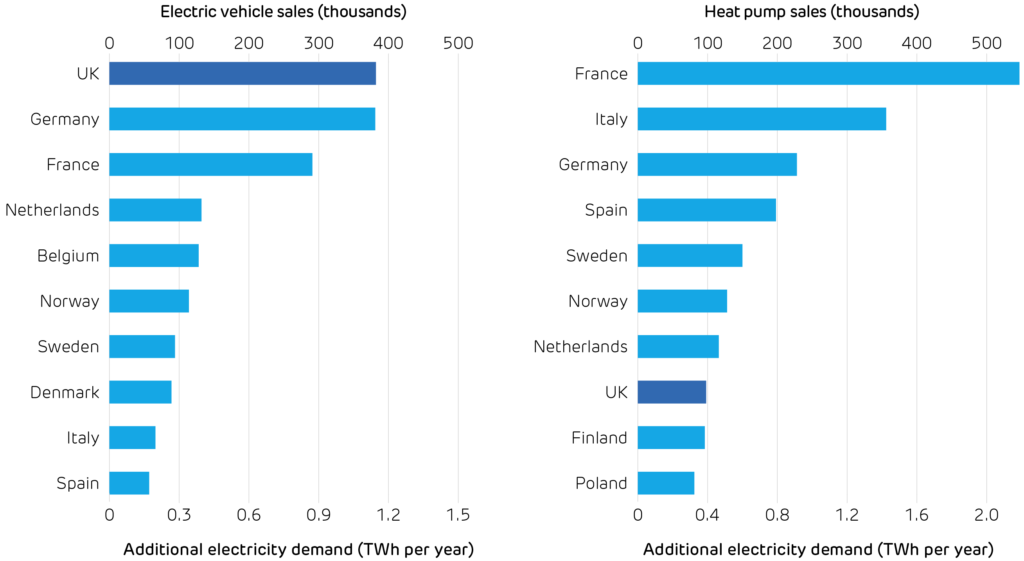

The UK is electrifying at a record pace. Last year, 382 thousand electric vehicles rolled onto our roads, just shy of 1 in every 5 cars sold. The UK took Germany’s crown as Europe’s largest market for electric vehicles (EVs) for the first time, after withdrawal of the ‘Umweltbonus’ made German sales plunge. It was a similar story for heat pumps: while sales on the continent shrank by a fifth, the UK market surged by 63%. With over 98,000 homes installing a heat pump last year, the UK finally became one of Europe’s top ten markets.

Faster uptake of electric heat and transport is critical for both decarbonisation and energy security, as transport and heating account for over 40% of national CO2 emissions, and nearly half of the gas and oil we consume is imported. However, all these new devices will impact electricity demand, especially at peak times.

These successes can both be traced to three policies. The Zero Emission Vehicle mandate required 22% of new car registrations to be fully electric last year, rising to 28% this year. Manufacturers face a £15,000 fine for each car that misses this target. Nine in ten EV sales are company cars, thanks to the generous benefit-in-kind tax rebate on EVs. Britain has opted for tariff-free access to Chinese-made vehicles, unlike Europe or the US – so new models from BYD, SAIC and others are keenly priced. On the heating side, heat pumps are being made more attractive by the £7,500 Boiler Upgrade Scheme voucher and zero VAT, while the Clean Heat Market Mechanism requires boiler makers to earn heat-pump “credits”.

What does this mean for the grid? A typical EV drinks about 3,000 kWh of electricity a year, slightly more than an average household. A family-sized heat pump adds another 4,000 kWh. Add up the new devices sold in 2024 and the extra demand comes to about 1.5 TWh per year, or just half a percent of Britain’s annual total demand. Their overall energy consumption is not a worry, but its timing is everything.

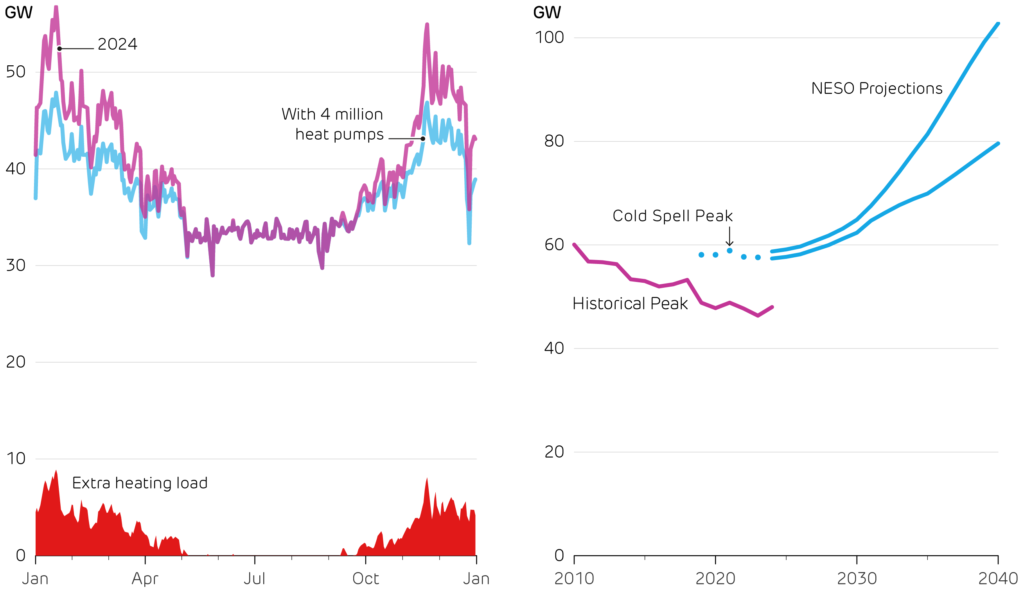

Electric vehicle and heat pump sales across the ten largest markets in Europe in 2024, with their impact on annual electricity demand. Data from ACEA and EHPA.

Britain’s electricity demand peaks at around 50 GW on frosty weekday evenings. These are exactly the times when heat pumps will run flat-out, so an extra 100,000 systems could add up to 1 GW to this peak. The National Infrastructure Commission forecasts heat pumps and EVs will more than double peak demand in 2050, adding 66 GW. New demand is being concentrated in the very hours the system is already strained the most. Cold snaps hurt twice: they push up heating demand just as heat pump efficiency (its coefficient of performance) drops, and they shorten the range of EVs (as energy is used on cabin heating), meaning people charge more frequently on the coldest days.

Policy is one step ahead in dealing with this. Since 2022 every new home or workplace charger must ship with a default overnight schedule and randomised start time to prevent synchronised surges, and similar “smart heat” standards are in consultation. Vehicle-to-grid pilots are scaling, and grid-scale battery storage has quickly risen to 6 GW installed, with another 8 GW under construction. Dynamic tariffs for households are becoming more common, paying households to soak up midday solar and avoid the evening crunch.

Looking forwards, electrifying heating and transport is indispensable, but it must be done smartly. As sales continue to grow, keeping peaks under control will hinge on faster battery build-out, agile tariffs and a distribution network fit for bidirectional power flows. Done right, low-carbon electricity will be key to cutting emissions and cutting bills, without cutting comfort.

Daily peak electricity demand across weekdays in 2024,

compared to with 4 million extra heat pumps operating (as

NESO’s net-zero scenarios expect by 2030). We estimate

these would push up peak demand by 18%.

Historical peak electricity demand over the last 15 years,

and expected future peak demand in the NESO Future

Energy Scenarios. These are higher in part because they

include contingency for an extreme cold spell.