What do heat waves do to the power system

The UK, Western Europe, Japan and parts of China saw their warmest June on record in 2025. Rising temperatures place growing strain on both public health and power systems. Across the world, 500,000 heat-related deaths occur each year, with 1,300 excess deaths in the UK alone last summer. The heat also lowers people’s productivity, with hot days (above 28°C) costing the UK economy an average of £1.2 billion per year.

Alleviating heat stress requires that homes and businesses are cooled to a comfortable temperature. Across the UK, rising temperatures mean the need for cooling is rising by 3% per year. In London, this is growing by 5% per year, faster than anywhere in the world. This is leading to more households purchasing air conditioners (ACs), as people no longer want to tolerate stiflingly hot nights.

The number of homes with ACs in the UK rose from 3% to 20% between 2011 and 2023, with a huge leap following the UK’s record-breaking 2022 heatwave. The Government are considering plans to extend the £7,500 grant for heat pumps to cover air-to-air systems, capable of both heating and cooling homes, which could further accelerate uptake. Each additional degree also means ACs must work harder to maintain the same indoor temperature, further increasing the amount of electricity consumed by a growing stock of ACs.

This problem is not unique to the UK. AC usage is rising across Europe, and with it summer peaks in electricity demand. In France, a country with relatively low ownership, the June heatwave saw peak electricity demand soar 25% above the typical off-season average.

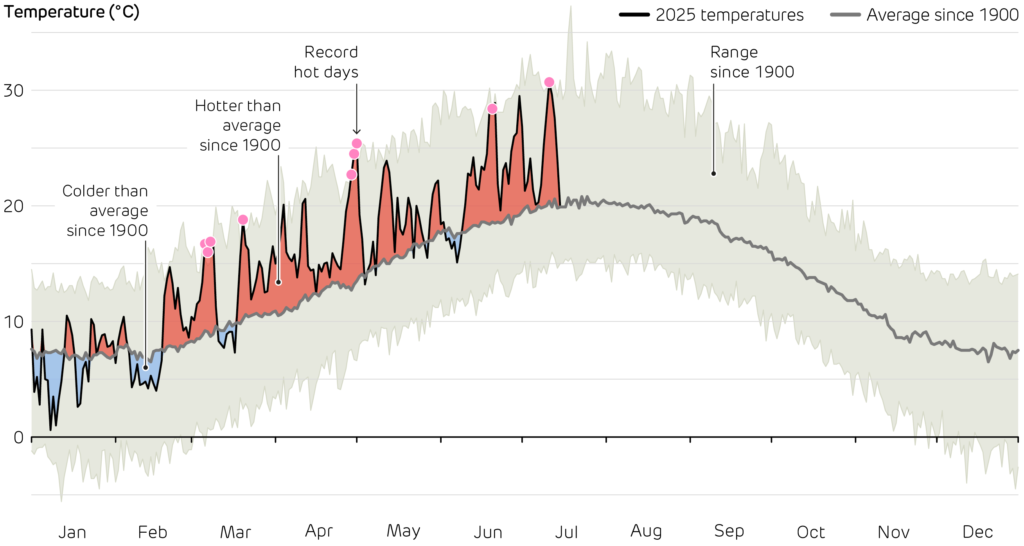

Maximum daily temperatures in central England this year compared to the range of temperatures seen since 1900.

Thankfully, when it is hot and people need cooling the most, the sun is shining. Britain’s solar panels produce 40% more electricity on days that reach above 25 °C compared to days that don’t get above 20 °C. This means that when ACs are

running flat out, they can tap into a cheap and low-carbon electricity, minimising the grid and emissions impacts.

Rising temperatures still bring challenges for electricity supply. Transmission cables expand and sag in the heat, increasing the risk of faults and reducing the amount of power they can conduct by up to a tenth. Maintaining grid reliability as the UK warms will require improved cooling methods, upgrading to higher-capacity transmission and distribution cables, and updating asset ratings to reflect the impacts of climate change.

Power stations are also challenged by extreme heat. During June’s Mediterranean heatwave, all but one of France’s 18 nuclear reactors had to reduce output as river temperatures soared to 5°C above normal, meaning they could not be used for cooling. Overall, French nuclear output falls by more than 5 GW when daily-average temperatures rise above 24°C, despite elevated demand. Power stations also become less efficient on hot days as less efficient steam cooling reduces turbine output. Even solar panels are affected by the heat, as high temperatures reduce their efficiency in converting sunlight into power.

Britain must face the reality that it is now a hot country, with rising temperatures reshaping daily life and electricity use. Adapting to this new norm means building a robust electricity system capable of meeting growing summer demand and coping with extreme heat, all while reducing emissions.

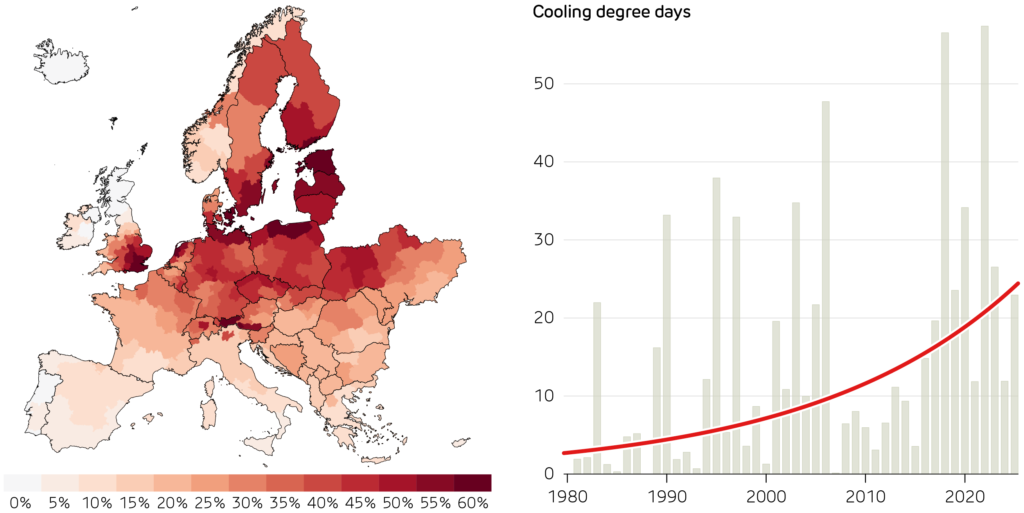

Cooling degree days (CDD) measure the need for air conditioning by combining how hot it is and for how long.

Left: a map showing how rapidly annual CDDs are increasing per decade across Europe since 1980.

Right: the evolution of annual CDDs in London, where they are rising fastest in the world