Wind becomes Britain’s largest source of electricity in 2024

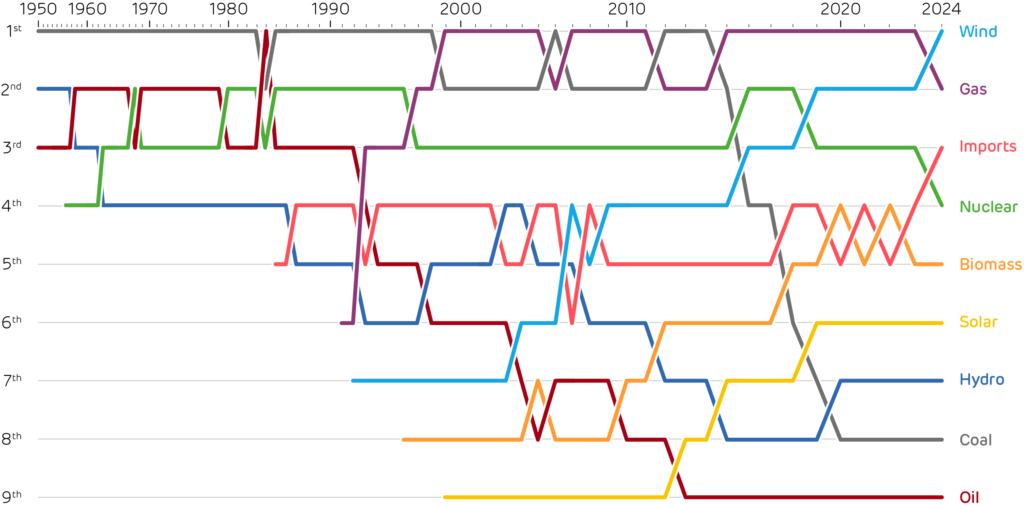

2024 was another landmark year for Britain’s power system. Wind became the largest source of electricity, the first time in its 140-year history that a fossil fuel was not in the top spot. Going right back to the foundation of our electricity system, coal was the largest source of generation each year until the 1984 miner’s strikes. Since then, either gas, oil or coal has produced the most electricity, until finally in 2024 a form of clean power became the single largest source.

Imports also overtook nuclear power to become the third largest source of electricity for the first time ever. Nuclear power was pushed down to 4th place, something not seen since 1962. Its 38 TWh of electricity production was up very slightly on last year, but still 40% lower than a decade ago. In contrast, biomass output increased 40% last year, but remained in 5th place.

The growth in renewables and decline of fossil fuels enabled power sector carbon emissions to fall by 15%. Electricity consumed in Britain emitted just 121 g/kWh last year. Electricity prices also fell by a quarter year-on-year, with wholesale power averaging £71/MWh, plus £11/MWh for the balancing services needed to keep the grid stable. While this is now lower than any time since 2018, prices are still well above the 2010s average of £45 plus £2/MWh.

Wind produced 83 TWh over the year, or 31% of the electricity consumed in Britain. This was up only slightly on 2023, so wind taking the top spot was more a story about the downfall of gas. Output from gas-fired power stations fell 16% year-on-year, as they lost out to growing imports and biomass generation.

Britain’s sources of electricity, ranked by annual production.

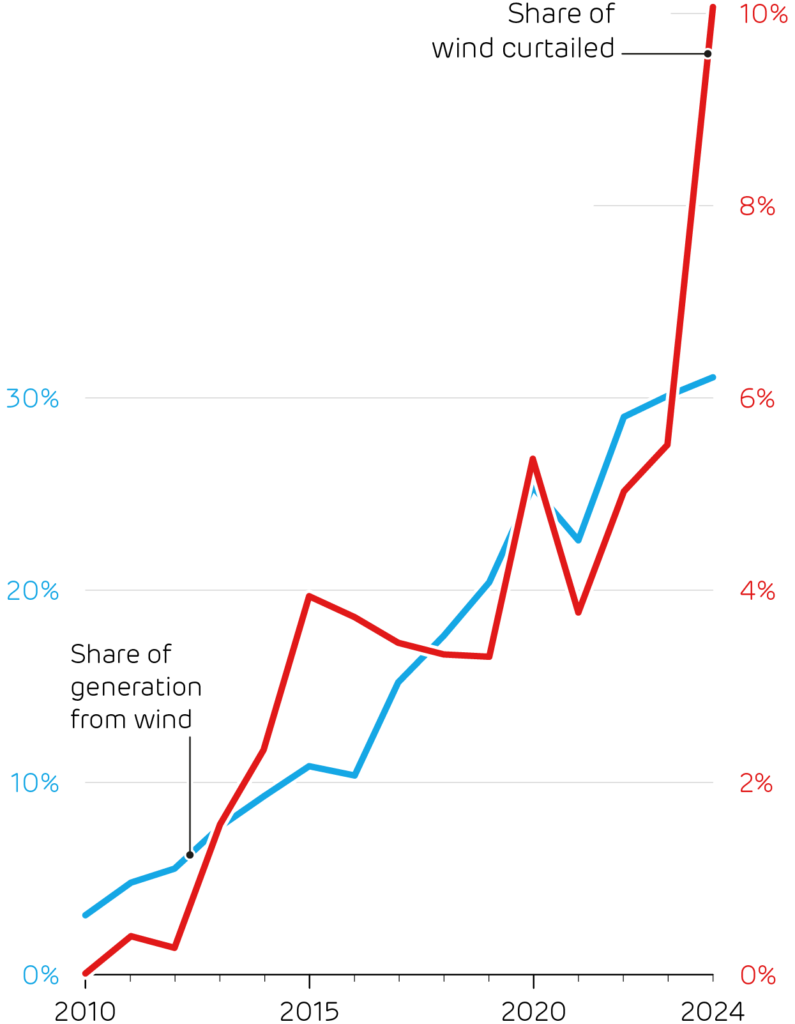

Output from our wind farms could have been much higher, but 10% of their generation in 2024 was curtailed. Some 8.3 TWh of wind energy had to be rejected from the grid as there was not enough transmission capacity to move power to where it was needed. This came at a high cost: £393 million spent over the year (or £14 per household), the highest on record.

Wind curtailment has generally risen in line with the amount of wind energy produced. Last year saw a sharp break in this trend though, with curtailment rates jumping from 5.5% to over 10%. Wind capacity in Scotland has risen more rapidly in recent years, but the transmission links which carry output down to demand centres in England have failed to keep pace and are now heavily congested. SeaGreen wind farm is a prime example of the consequence. A 1 GW farm off the coast of Angus in Scotland, SeaGreen came online late in 2023, but last year 70% of its electricity was wasted due to grid congestion. More transmission and storage in Scotland would help reduce this wastage, as would higher demand from Scottish industries and households.

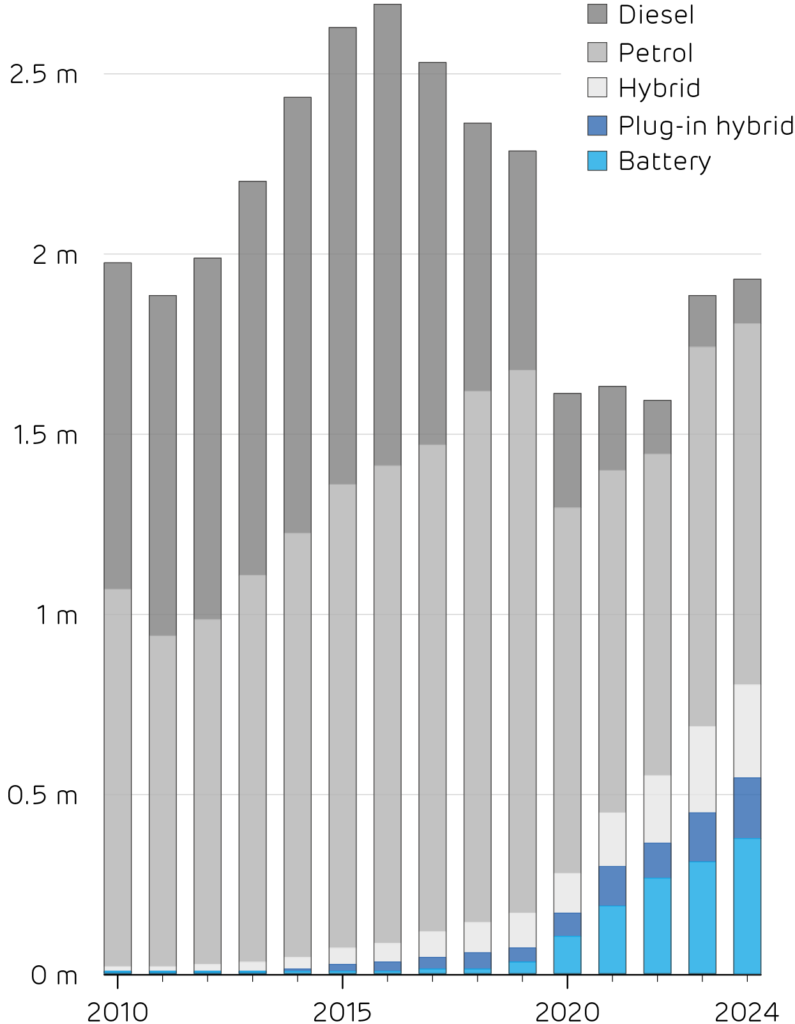

Britain’s electricity demand grew by 1.6% in 2024. While that may not sound much, it is the fastest year-on-year growth since 2010, apart from the post-Covid rebound. Alongside new technologies such as AI, electric vehicles have a part to play in this. More than half a million battery and plug-in hybrid vehicles were sold in the UK last year. Recharging these vehicles is consuming over 1 TWh of extra electricity per year, while saving around 2.5 million barrels of oil per year (~£150 m), and nearly half of UK oil consumption is imported.

The rise of wind power and wind curtailment.

Sales of new vehicles in the UK, split by type.