Oil and gas in an over-supplied world

Oil is the world’s largest source of energy, and never far from the news. December and January saw global geopolitics flare up, with major disruptions in Venezuela and Iran. These short-term shocks mask the wider story of ‘demand displacement’. Renewables are displacing gas and coal burnt for electricity while electric vehicles reduce the oil needed for transportation. Looming oversupply of fossil fuels suggests that lower prices could be a prospect for this coming year.

Speed versus stamina

The US is the world’s largest producer of oil and gas. It supplies two-thirds more oil than 2nd ranked Saudia Arabia, and two-thirds more gas than 2nd ranked Russia. Their ‘energy dominance’ was driven by the shale revolution, where hydraulic fracturing – or ‘fracking’ – unlocked vast oil and gas resources trapped inside rock formations. This allowed US fossil fuel supply to rapidly expand, but their remaining reserves are now waning fast.

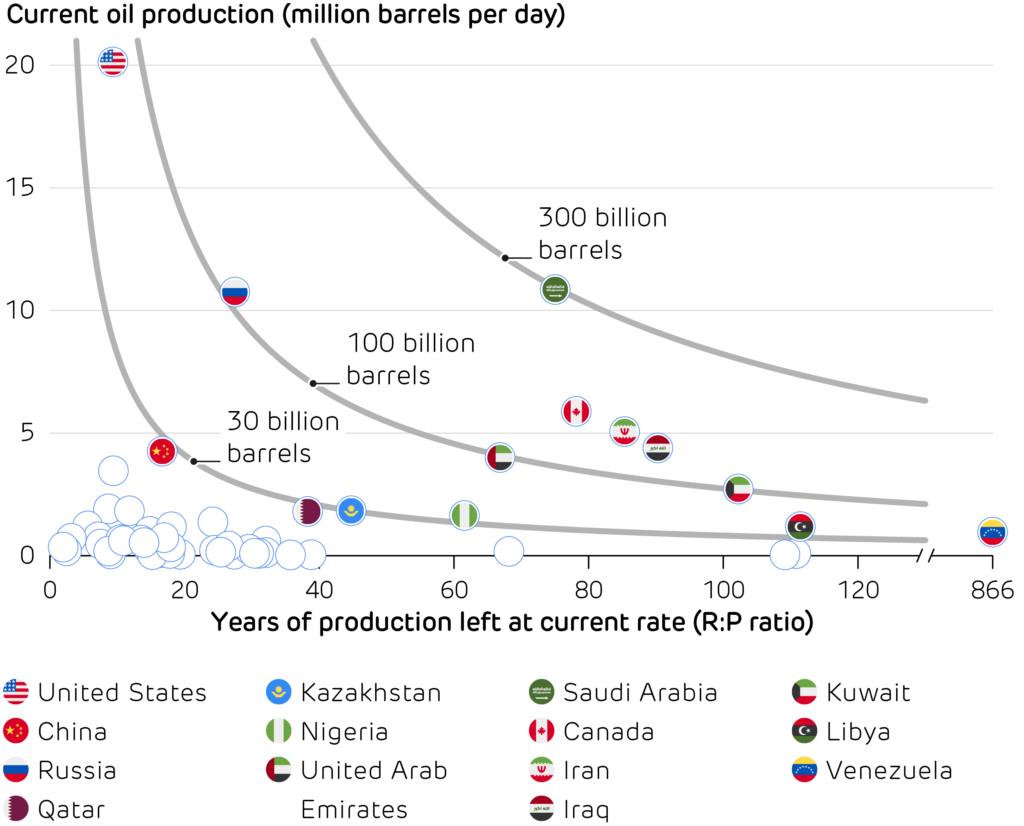

The ratio between a country’s oil reserves and its production – known as the R:P ratio – gives an estimate of how long production can continue at current rates. The US sits at one end of the spectrum, burning bright for a short time. Venezuela sits at the opposite end, with the world’s largest oil reserves but very limited production because of chronic underinvestment and international sanctions.

Speed versus stamina in the global oil market. The US is the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas liquids by a wide margin, but it can only keep up this pace for the next decade before its current reserves are exhausted. Other large producers, such as Saudi Arabia, Iran and Canada could continue producing at current levels until the end of this century. Venezuela stands apart from the pack, being able to continue producing at its current (reduced) rate until we approach the year 2900.

Short-term disruption

Recent geopolitical disruptions surround the global oil market. Venezuela is in a fragile transition after a US raid in January captured President Nicolás Maduro and opened up Venezuela’s oil sector to foreign investors. Iran is experiencing widespread anti-government protests with renewed US threats of intervention raising concerns about supply disruptions. These events contributed to oil prices climbing 14% in January. If Iran’s supply was lost from the market, oil prices would spike by 30% in the short term and as much as 60% by year-end, according to BloombergNEF.. Oil is not directly relevant for UK electricity, as it is used for less than 1% of supply, but oil and gas prices tend to track one another. Changes in oil prices would be strongly felt at the petrol pump, and more broadly, oil affects inflation and the national trade deficit.

Long-term excess

Short-term supply disruptions could give way to the bigger picture of falling demand. Electric vehicles are saving 1.3 million barrels of oil per day, equivalent to Venezuela being taken offline. As sales are growing rapidly around the world, this is expected to quadruple to 5 million barrels by 2030. Oil demand has flatlined in the US since 2020, while the UK’s oil demand peaked back in 1973, and has since fallen 40%.

Much of the oil industry faces a dilemma: if we move into a peak demand world, it is not clear who will buy all the oil currently being produced. One thing is clear – if we are to meet global decarbonisation objectives, much of the oil that we know about must be left in the ground.

The same is true for gas. Supply constraints in 2025 meant that gas prices reach their highest levels since the energy crisis of 2022. Booming liquid natural gas (LNG) exports saw US gas prices rise, making coal-fired electricity more competitive, increasing American coal burn for the first time since 2021.

Impact on bills

A large new wave of LNG capacity is coming online in the next year, with IEA and Reuters forecasting a global glut. LNG export terminals are springing up around the world, with LNG trade expected to increase by 7%. Gas prices in Europe and the UK remain more than twice as high as those in the US, so greater trade holds the promise of both reducing and stabilising prices in future.

Cheaper gas means lower energy bills to come, especially as Britain’s electricity prices are almost entirely dictated by gas prices. Volatility is a bigger threat than price level: one geopolitical shock can still send energy prices spiralling, which strengthens the case for a diversified electricity mix. Cheaper fossil fuels also raise the risk of undoing progress on reducing carbon emissions: any relief on bills should not be an excuse to lock in another decade of oil and gas dependence.