The growing influence of Britain’s weather on its electricity

A grey, still Wednesday in January revealed how the weather now calls the shots on Britain’s power system. Real-time prices spiked to over seven times the winter average (an eye-watering £2,900/MWh), and the system operator spent £21 million balancing supply and demand that day. The Royal Meteorological Society’s latest “State of the Climate for the UK Energy Sector” report shows how weather-driven changes in renewable output and demand drive power prices, and how extreme weather events increasingly impact on our energy infrastructure.

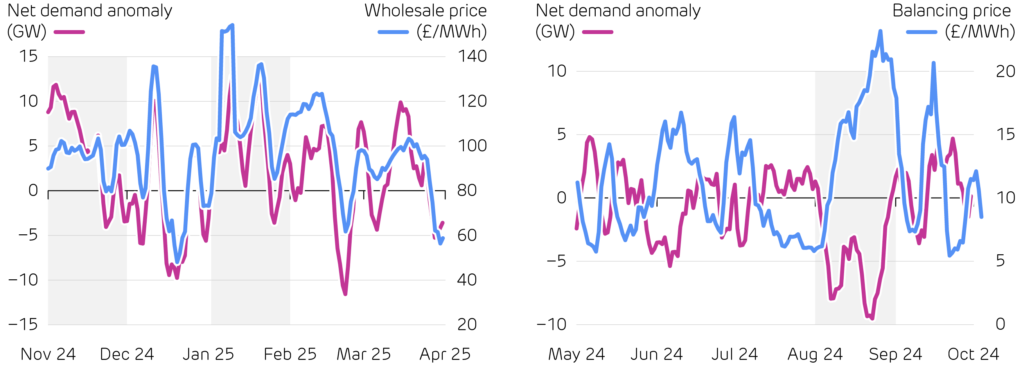

Throughout November 2024, calm and cloudy conditions led to below-average wind and solar generation. Fortunately, the long wind drought coincided with mild temperatures that reduced demand for electricity, muting price impacts. Similar conditions during January 2025 combined with freezing conditions in a so-called “dunkelflaute”event which led to large spikes in the wholesale price. Despite tight margins, there was no disruption to supplies as the National Energy System Operator (NESO) used interconnectors, stored energy and fast-start gas to balance supply and demand.

High winds and sunny skies led to the opposite problem in summer. Too much wind and solar generation through August 2024 meant that while wholesale prices were low, keeping the grid in balance was more difficult, and thus more expensive. Wind farms were required to curtail their output extensively, at a cost of over £40 million (the highest monthly total on record). This raises balancing costs which ultimately filter through to consumers.

The weather not only moves prices, but is increasingly damaging Britain’s energy infrastructure. Seven named storms hit the UK over the 2024–25 season (April to April). Storm Darragh (6–7 December 2024) left 2.3 million customers without power across Wales and central and northern England, while Storm Eowyn (24 January 2025) left >1 million customers disconnected across Scotland and northern England. Most faults were caused by high winds and/or flooding damage. Localised outages were also caused by extreme rainfall during the summer, and lightning damage during heavy thunderstorms in May.

When renewable output is low and demand is high over winter, wholesale power prices can spike. Net demand refers to electricity demand minus output from wind and solar, and its anomaly means how far net demand deviates from its long-term average. In contrast, balancing costs can spike during the opposite conditions in summer: when renewable output is high and demand is low.

Weather variability will become increasingly important

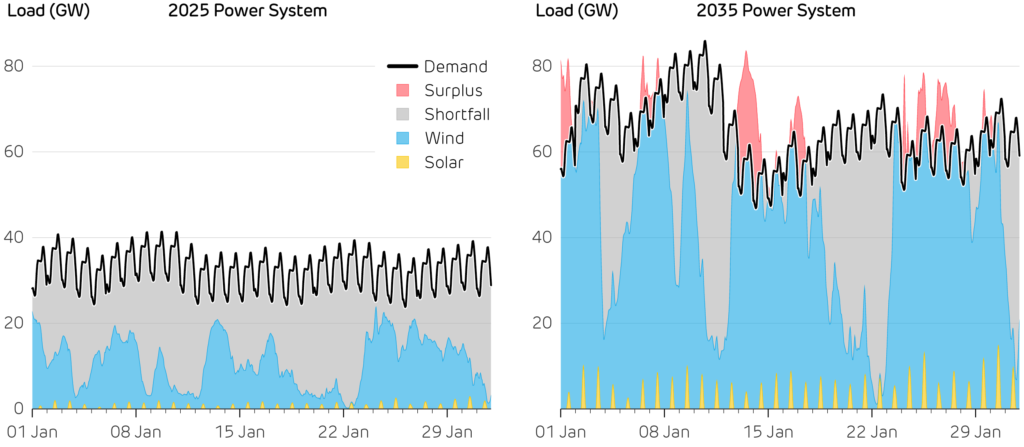

By 2035, wind and solar capacity is expected to more than triple, and electricity demand would be >50% higher as we electrify transport (via electric vehicles) and heating (via heat pumps). The RMetS report tests the resilience of the future power system, by modelling how the “dunkelflaute” events of January 2025 would play out. These conditions would be even more challenging for our future clean power system, as higher demand (from electrified heating) would coincide with stalled output from renewables.

Simply building more wind and solar farms is not enough. Even with triple the current capacity, their output would remain minimal on the bleakest days. In 2025 we faced a 35 GW gap between supply from wind / solar and electricity demand, which could be met by the nation’s fleet of gas-fired power stations. By 2035 this becomes a 75 GW gap – impossible to meet with our current fleet of power stations. To plug the gap, new technologies are needed: stronger interconnectors, ways to make demand flexible, firm low-carbon generation, and longer-duration types of energy storage, such as pumped hydropower and green hydrogen (see Article 4). One key opportunity for the future power system is the ability to store excess electricity when conditions are favourable (such as on 13 January when it was windy and mild), to be used later when conditions are more challenging (such as the following week when wind output fell close to zero).

Weather’s impact on electricity is no longer background noise, it is the driving force behind both prices and outages. As supply and demand become increasingly swayed by the elements, weather-dependent cold, calm, dark spells become the power system’s defining tests. The answer is to hedge this risk across both time and space by building in flexibility to harden our power system against future challenges.

The mismatch between demand for electricity and supply from weather-driven renewables during January 2025 (left), and simulated for the power system in 2035 (right). The the red and grey shaded areas show demand net of renewables, which is a core metric that determines how much flexibility is required to ‘top up’ wind and solar or reduce demand to keep the lights on – the higher the value, the more flexible the system needs to be.