Battery storage soars, long-duration storage is next

Energy storage is essential to keep any clean power system running smoothly. Unlike traditional power plants, wind and solar farms cannot be ‘dispatched’ to meet demand, so storing energy in periods of high renewable output and releasing it when needed is a key pillar of the UK’s Clean Power Mission.

Battery energy storage systems (BESS) are now Britain’s largest form of energy storage. They use the same core technology as mobile phones and electric vehicles (lithium-ion cells), but on a much larger scale. Installed. BESS capacity has risen sharply over the past decade, from almost nothing in 2015 to over 6 GW today, enough to power 1.3 million homes for a day. BESS operators now make most of their money via arbitrage – buying low and selling high – but they can also “stack” revenues across other grid services (e.g. also providing balancing and frequency response). Falling battery costs and Britain’s grid lagging behind renewables expansion have created attractive investments.

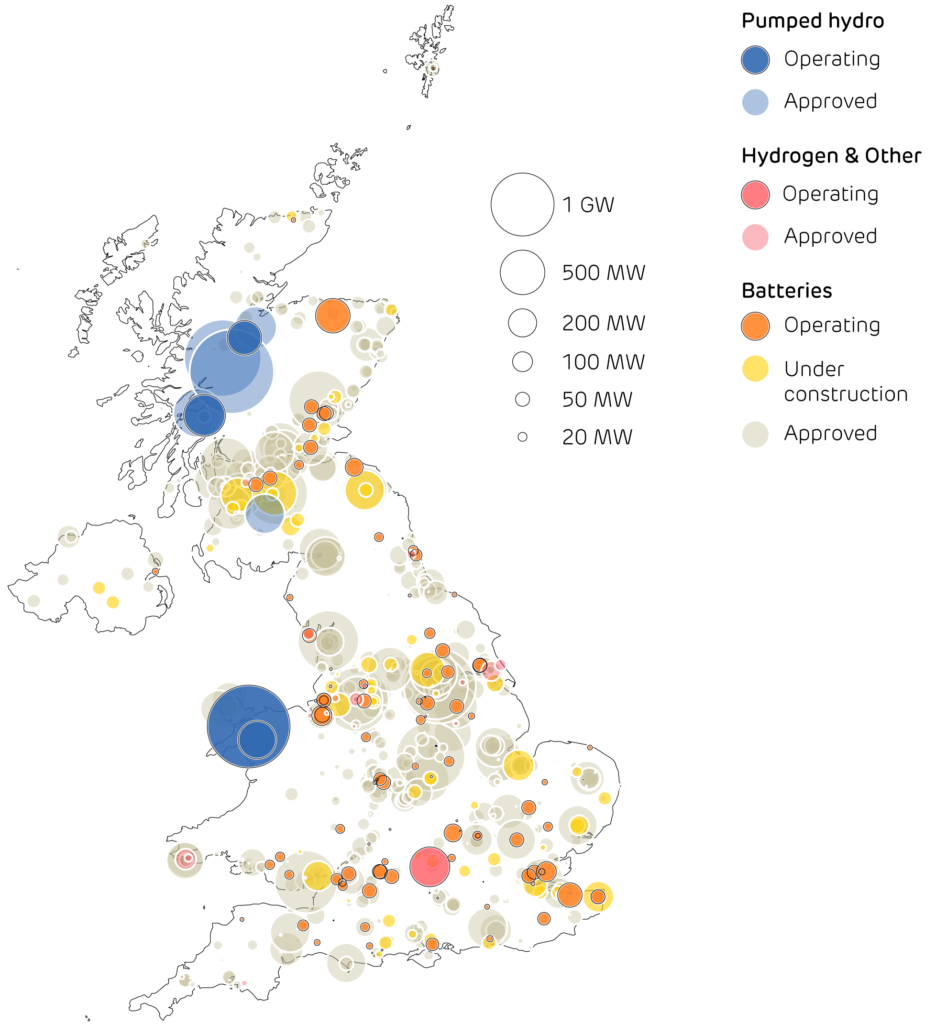

The UK’s current and future energy storage infrastructure, separated by the class of technology and stage of project development.

The Government expects 23–27 GW of BESS will be needed by 2030 in their Clean Power Action Plan, three to four times current capacity. Industry is well equipped to deliver this, with 45 GW of battery projects consented or under construction. Most existing projects are in England, but Scotland has become a key growth area due to high wind output and tight network constraints (see Article 3).

The UK’s largest battery is in Moray, Scotland, with 200 MW of power and 400 MWh of energy capacity, and another 100 MW due to be added in 2026. It was built to ease congestion from nearby offshore wind farms, and could power 50,000 homes for a day. The UK’s National Wealth Fund is also planning a £500 million joint venture to deliver 1.4 GW of storage by 2028, with the first projects in Angus, Perth and Kinross.

Batteries can only hold a few hours’ worth of electricity. The Moray battery fully charges or discharges in just 2 hours. This means batteries pair well with solar PV’s daynight cycle. On the other hand, the UK’s wind output varies over days and weeks, while heating demand is highly seasonal. Mediumduration and long-duration storage (MDES and LDES) are needed to support the future energy system, and cut our reliance on firing up expansive gas power plants to fill these gaps. The Government anticipates 4–6 GW are needed by 2030 in their Clean Power Action Plan (rising to 11–15 GW by 2050).

The closest we currently have to long-duration energy storage is 2.8 GW of pumped hydroelectric storage, spread across four sites in Wales and Scotland. These use surplus electricity to pump water uphill and release it again to generate electricity when needed. These date from the 1960s to 1980s, and no new pumped hydro has been built in the UK for forty years. A wave of new developments are planned though, with 11 new projects at various stages of development in Scotland and Wales, which could add a combined 10 GW of capacity (200 GWh of energy), one-quarter of Britain’s daily demand.

Hydrogen is also a potential option for long-duration energy storage, which could last for weeks or months. Hydrogen can be produced by splitting water using wind or solar power, with the Government targeting 10 GW of low-carbon hydrogen production by 2030. Liquid-air, compressed-air, iron-air batteries, storing heat underground in aquifers, and a whole host of other technologies offer promising options to ride through longer shortfalls in supply.

Unlike BESS, long-duration storage does not present an obvious investment opportunity. Long-duration technologies are more expensive as it is more difficult to store electricity for long periods. They also charge and discharge less frequently (seasonal cycles rather than daily cycles), reducing arbitrage opportunities. Incentives are needed to encourage investment. The Planning and Infrastructure Bill introduced a “cap and floor” scheme to de-risk investments by topping up profits earned by long-duration storage (>8 hours) if they are low (and clawing them back if they are excessive). Applications opened this year and contracted 3–8 GW by 2035. Ofgem has waved a further 77 projects (29 GW) through to the final stage of assessment of the Government’s ‘super battery’ support scheme.

Together with grid expansion and more interconnection, storage is the glue that can hold together abundant renewables and reliable, affordable power. Batteries and long-duration storage solve different problems and need different support. Backing both types of technology, Britain can reduce its reliance on expensive gas, improve energy security, and make clean power dependable year-round.