The Great Grid Upgrade

Earlier this year, National Grid announced the Great Grid Upgrade: 17 projects that form the largest overhaul since the creation of our modern ‘supergrid’ in the 1960s. New offshore interconnectors and targeted upgrades to onshore networks, pylons and substations will strengthen the links between Scotland, England and the North Sea to move clean power from where it is generated to where it is needed. At a cost of £19bn, this expansion represents two-thirds of National Grid’s planned investments to 2030.

Britain’s grid was originally built to transmit electricity from centralised power stations to nearby towns and cities, but the way we produce and use power is changing rapidly. Wind power now provides 30% of Britain’s electricity, but is concentrated in windy Scotland and the North Sea, while demand is highest in the densely-populated South East.

Demand for electricity is also set to rise by 50% by 2035 as we turn to electricity for heat and transport, while new AI and data centres come online. This means even more electricity must be shifted around the country. Today, congested transmission lines mean we cannot use all the electricity we generate. This comes at a cost, with consumers paying >£1 billion so far this year to curtail wind farm output that could not be used. With network upgrades, more clean electricity can be used, lowering bills for everyone.

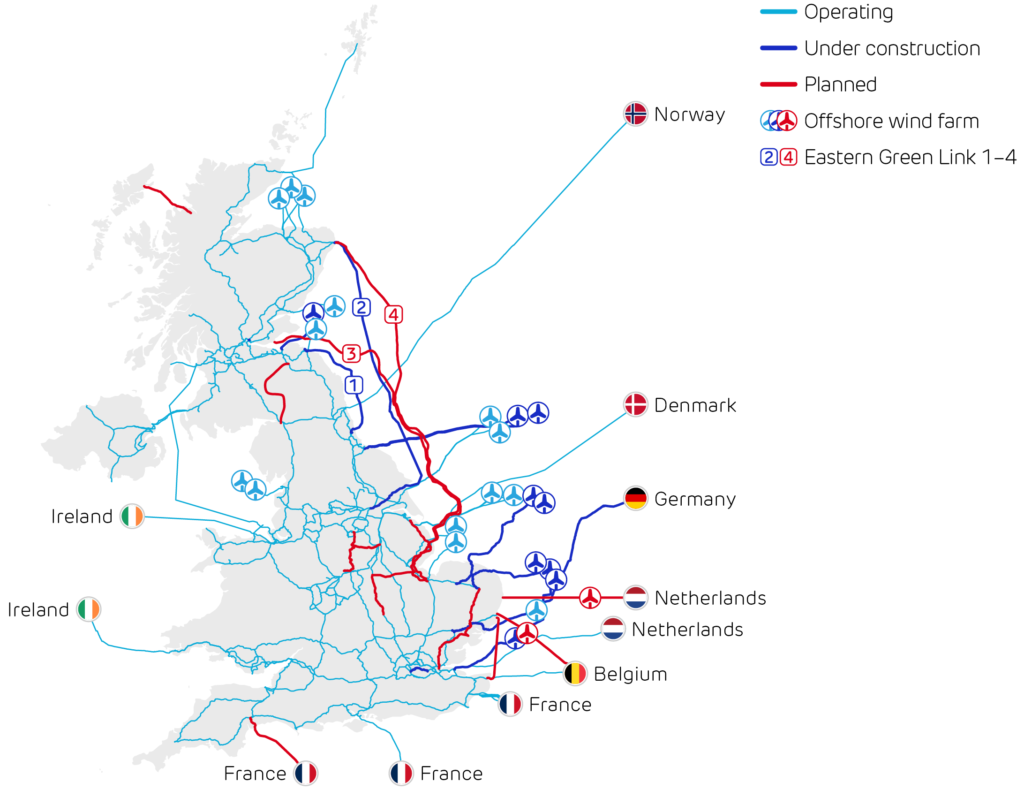

The UK’s high voltage electricity transmission network, and interconnectors to neighbouring countries. The Great Grid Upgrade and other planned projects are highlighted in red. Data from OpenStreetMap via OpenInfraMap.

Upgrading electricity networks is like building roads: the more routes there are available, the less likely you will hit traffic on any one route. The Great Grid Upgrade includes four new subsea cables (Eastern Green Links 1–4) to connect Scotland’s wind farms to the South and East of England. Other projects include the Sea Link cable from Suffolk to Kent to carry power from the planned Sizewell C nuclear reactor, and reinforcements to various lines throughout the country.

In addition, new interconnectors to France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany are planned or under construction, to help smooth out supply and demand over the wider continent. These include Nautilus (to Belgium) and LionLink (to the Netherlands), so-called “offshore hybrid assets”, which also connect to offshore wind farms, meaning that power can be sent to whichever country needs it more.

Most of the UK’s network upgrades are still in the planning stages, with onshore projects facing strong opposition from local groups concerned about the visual and environmental impacts of pylons. The Norwich-Tilbury transmission line received over 20,000 pieces of community feedback since its consultation launched in 2022, and 40,000 people signed a petition calling for less visible alternatives, resulting in 10% of the line being replaced with underground cables. Similar factors also led to the de-facto ban on onshore wind from 2015–2024, despite it offering the cheapest form of new-build electricity in the UK.

Opposition to new transmission pushes up the cost of electricity, as the alternatives of underground and offshore cables are 4.5 and 11 times more expensive than traditional overhead lines. Extensive delays in planning mean the problem (and cost) of curtailment stays with us for longer. Both the Government and National Grid have rejected large-scale underground cabling, with the Government instead proposing that residents near new pylons receive up to £2,500 off their energy bills over the next decade.

In the short term, the Great Grid Upgrade will mean construction traffic, new pylons on the skyline and billions in upfront costs. But we can learn from the Victorians, who built big with railways and sewer systems that caused disruption at the time, but created a legacy that benefitted the UK for a century since. Rather than continuing to pay to throw clean energy away, then pay again to replace it where it’s needed; it is time to build a grid that can see us through for decades to come.